~~Mahatma Gandhi A Real Hero Of Independence~~

Full Nane & Born:- Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

2 October 1869 Porbandar, India

2 October 1869 Porbandar, India

Nick Name:- ( Mahatma Gandhi, Bapu, Gandhiji)

Nationality:- Indian

Parents:- Putlabai Gandhi (Mother)

Karamchand Gandhi (Father)

Parents:- Putlabai Gandhi (Mother)

Karamchand Gandhi (Father)

Children:- Harilal

Manilal

Ramdas

Devadas

Manilal

Ramdas

Devadas

Spouse(s):- Kasturba Gandhi

Date Of Death:- 30 January,1948

Delhi, India (assassination)

************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Best Known For:- Mahatmas Gandhi was the primary leader of India's

independence movement and also the architect of a form

of civil disobedience that would influence the world.

Ethnicity:- Gujarati

Date Of Death:- 30 January,1948

Delhi, India (assassination)

************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Mahatma Gandhi Father Karamchand Gandhi Mahatma Gandhi Mother Putlibai Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi Stamps

First Online: September 02, 2009

Page Last Updated: June 13, 2013

Page Last Updated: June 13, 2013

Here is a collection of stamps depicting Mohandas K. Gandhi, the apostle of peace.

|

|

Mahatma Gandhi& Kasturba Gandhi Kasturba Bai, was the mother figure in Mahatma Gandhi's Ashram and she was greatly influenced by the vision and routine of his lifestyle, so much so she broke the barriers of a strict traditional upbringing by removing the feeling of 'untouchability' from her mind and behaviour. Few knew that she went with the Mahatma to prison many times and died in prison at Pune. On her death Rs one crore and twenty five lakhs was presented to Gandhi who in turn formed a 'Charitable Trust' in her memory for women. |

The Mahatma Gandhi's marriage is a reflection of an 'ideal' relationship which is based on 'true friendship', where it is more important to accept and support what your friend is doing, rather than expect and demand from him or her !

|

| Mahatma Gandhi Wife Kasturba Gandhi With Her Sons Harilal Gandhi, Manilal Gandhi, Ramdas Gandhi & Devdas Gandhi |

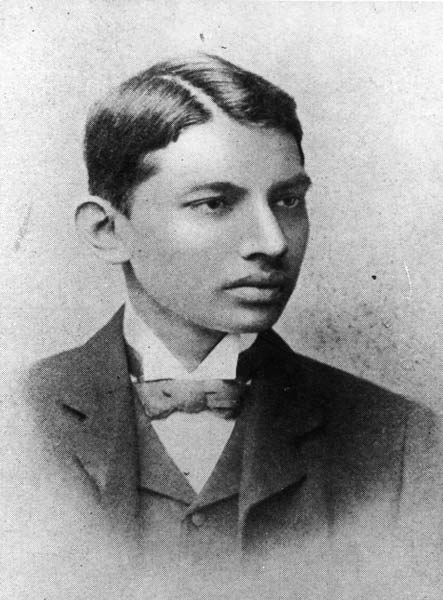

Image Fore Mahatma Gandhi Childhood:-

|

%2520of%2520family%2520and%2520cricket%2520photos%2520with%2520duplicate%2520069.jpg)

|

| With his brother, Laxmidas, 1886 |

Biography:-

|

The word Mahatma means great soul. This name was not given Gandhi at birth by his parents, but many years later by the Indian people when they discovered they had a Mahatma in their midst. |

Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a small state in western India. He was named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The word Gandhi means grocer, and generations earlier that had been the family occupation. But Gandhi's grandfather, father, and uncle had served as prime ministers to the princes of Porbandar and other tiny Indian states, and though lower caste, the Gandhis were middle-class, cultured, and deeply religious Hindus.Gandhi remembered his father as truthful, brave, incorruptible, and short-tempered, but he remembered his mother as a saint. She often fasted for long periods, and once, during the four months of the rainy season, ate only on the rare days that the sun shone.

At the age of six Gandhi went to school in Porbandar and had difficulty learning to multiply. The following year his family moved to Rajkot where he remained a mediocre student, so sensitive that he ran home from school for fear the other boys might make fun of him. When Gandhi was thirteen, he was married to Kasturbai, a girl of the same age. Child marriages, arranged by the parents, were then common in India, and since Hindu weddings were elegant, expensive affairs, the Gandhi family decided to marry off Gandhi, his older brother, and a cousin all at one time to spare the cost of three separate celebrations. At first the thirteen-year-old couple were almost too shy to speak to each other, but Gandhi soon became bossy and jealous. Kasturbai could not even play with her friends without his permission and often he would refuse it. But she was not easily cowed, and when she disobeyed him the two children would quarrel and not talk for days. Yet while Gandhi was desperately trying to assert his authority as a husband he remained a boy, so afraid of the dark that he had to sleep with a light on in his room though he was ashamed to explain this to Kasturbai. The young bridegroom was still in high school, where his scholarship had improved, and he won several small prizes. Indian independence was the dream of every student, and a Moslem friend convinced Gandhi that the British were able to rule India only because they ate meat and the Hindus did not. In meat lay strength and in strength lay freedom.Gandhi's family was sternly vegetarian, but the boy's patriotism vanquished his scruples. One day, in a hidden place by a river, his friend gave him some cooked goat's meat. To Gandhi it tasted like leather and he immediately became ill. That night he dreamed a live goat was bleating in his stomach, but he ate meat another half-dozen times, until he decided it was not worth the sin of lying to his parents. After they died, he thought, he would turn carnivorous and build up the strength to fight for freedom. Actually, he never ate meat again, and freed India with a strength that was moral rather than physical. But Gandhi was still a rebellious teenager, and once, when he needed money, stole a bit of gold from his brother's jewelry. The crime haunted him so that he finally confessed to his father, expecting him to be angry and violent. Instead the old man wept.

"Those pearl drops of love cleansed my heart," Gandhi later wrote, "and washed my sin away." It was his first insight into the impressive psychological power of ahimsa, or nonviolence. Gandhi was sixteen when his father died. Two years later the youth graduated from high school and enrolled in a small Indian college. But he disliked it and returned home after one term. A friend of the family then advised him to go to England where he could earn a law degree in three years and equip himself for eventual succession to his father's post as prime minister. Though he would have preferred to study medicine, the idea of going to England excited Gandhi. After he vowed he would not touch liquor, meat, or women, his mother gave him her blessing and his brother gave him the money. Leaving his wife and their infant son with his family in Rajkot, he went to Bombay. There he purchased some English-style clothing and sailed for England on September 4, 1888, just one month short of his nineteenth birthday.

Education:-

Young and handsome Gandhi

|

| Gandhi with his collegues in South Africa |

Mohandas Gandhi with his friends in South Africa

He trimmed his expenses by walking ten miles to school each day to save carfare, moving into a cheaper room, and preparing his own breakfasts of oatmeal and cocoa and dinners of bread and cocoa. He continued to eat lunch in vegetarian restaurants.All of his life, experiments with food were to be part of Gandhi's experiments with truth. While in England, where food is sometimes tasteless anyway, he decided he could do without condiments, for "the real seat of taste [is] not the tongue but the mind." He was an aggressive vegetarian and was elected to the executive committee of the local vegetarian society, which he founded. But he was so shy that he froze when he attempted to speak at meetings, and others had to read his speeches for him.During Gandhi's second year in England, two English brothers asked him to study the Bhagavad Gita, a part of the sacred Hindu scriptures, with them.

A long poem of some seven hundred stanzas, written several hundred years before Christ was born, the Gita is a dialogue between the Hindu god Krishna and Arjuna, a warrior about to go into battle.Gandhi had never before studied the Gita, either in English, or in its original Sanskrit, or in Gujarati, his own dialect. It glorifies action, renunciation, and worldly detachment, and its message seared Gandhi's soul. He later called the Gita his "dictionary of conduct" and turned to it for "a ready solution of all my troubles and trials."At about the same time he was searching through the Gita, a Christian friend persuaded Gandhi to read the Bible. The Old Testament set him dozing, but the New Testament, particularly Christ's Sermon on the Mount, evoked a spiritual recognition.Whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man take away thy coat let him have thy cloak too." The seeds of Gandhi's philosophy of renunciation and nonviolence were thus planted almost simultaneously by sacred Hindu and Christian texts.

|

| Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi as Lawyer |

Gandhi easily passed his law examinations, was called to the bar on June 10, 1891, enrolled to practice in the High Court on the 11th, and sailed for home on the 12th. He did not spend a day more in England than he had to. On the choppy passage back to India, twenty-one-year-old Gandhi was sick with doubt. He had learned some laws, but he had not learned how to be a lawyer. Besides, the laws he had learned were English; he still knew nothing of the Hindu or Moslem law of his own country. The despair he felt was doubled when his brother met him at the dock with the news that his adored mother had died while he was away. Gandhi returned to his family at Rajkot. He quarreled with his wife and played with his son, but he was unable to earn money to support them. Friends advised him to go to Bombay to study Indian law, but when he finally got his first case there he was too shy to cross-examine the opposing witnesses. He returned the fee and told his client to find another lawyer.

|

| Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa in 1895 |

Desperate, he tried to get a job teaching English in a high school, but he was rejected as unqualified. Defeated, he left Bombay and returned to Rajkot. Gandhi's brother, who was also a lawyer, routed enough paperwork to him to pay for his keep, but Gandhi hated the petty tasks, the local political intrigues, and the arrogance of the ruling British. Bitter and bewildered, he longed to escape from India.

His opportunity unexpectedly came when a large Indian firm in Porbandar asked him to go to South Africa to assist in a long and complex legal case in the courts there. It would take about a year and he would be paid all his expenses plus a salary. Gandhi accepted with joy. A second son had been born to Kasturbai since Gandhi's return from England almost two years earlier. Gandhi bade his growing family farewell and in April, 1893, not yet twenty-four years old, he set sail "to try my luck in South Africa." He found more than luck; he found himself, his philosophy, and his following.

South Africa The First Crusade:-

There were approximately sixty-five thousand Indians in South Africa at the end of the nineteenth century. The first had come as serfs bound to five years of plantation labor. When their term of bondage ended they were either shipped back to India or permitted to stay as free laborers. There were also thousands of free Indians of all classes, who had emigrated to South Africa. Some of them became wealthy and powerful. This outraged and frightened the Europeans, who would not consider colored men equals, and who contemptuously referred to the Indians as "coolies."

About a week after Gandhi arrived at Durban, in Natal, his business took him to Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal. His journey was an odyssey of discrimination and it set the direction of his life. He bought a first-class ticket and dressed, as he did then, in impeccable European clothing, traveled first-class until the train reached Maritzburg, the capital of Natal. There, a white passenger protested to railroad officials, and Gandhi was ordered to a lower-class compartment. He pointed to his first-class ticket and refused to move.

A policeman threw Gandhi and his luggage off the train, which continued its journey without him. He spent the night in the station's unlit, unheated waiting room. It was bitterly cold, but Gandhi's overcoat was in his luggage and his luggage was in the hands of the railroad authorities. Gandhi dared not request it for fear of being insulted again.

Instead, he sat shivering through the endless night, asking himself one question: Shall I fight for my rights or go back to India? By dawn he had made his decision. He would fight for his rights and the rights of all people.

Victory in South Africa:-

|

First, a group of women from Tolstoy Farm courted arrest by crossing from the Transvaal into Natal. Although this was illegal, they were not halted. Soon after, a group of women from the Phoenix settlement in Natal crossed the opposite way, into the Transvaal, and were arrested. Among them was Gandhi's wife Kasturbai. At first he had been unwilling to ask her to sacrifice herself, but she complained, "What defect is there in me which disqualifies me for jail?" and so Gandhi relented.Then the women who had crossed into Natal without having been arrested followed Gandhi's instructions and marched to the coal mInes at Newcastle. There they incited the Indian miners to strike against the annual tax on free laborers. At this point the women were imprisoned, and the cauldron started bubbling. Free Indians were outraged at the sight of the women they so carefully protected being tossed into jail. Serfs sympathized with the miners. Gandhi hurried to Newcastle to organize the strike. He suggested the men abandon the mines and return with him to the Transvaal and to prison. They agreed.

In one day, about five thousand men, with Gandhi in the lead, marched to Charlestown, the Natal village nearest the Transvaal border. Fed and sheltered by local Indians, they camped for several weeks as strikers came and went and Gandhi plotted his next move. He tried to arrange a peaceful settlement and called Smuts' office, telling the General's secretary, "If he promises to abolish the tax I will stop the march. Will not the General accede to such a small request?" The secretary checked with Smuts and replied, "General Smuts will have nothing to do with you. You may do as you please." At 6:30 on the morning of November 6, 1913, Gandhi set out with 2,037 men, 127 women, and 57 children. One mile from Charlestown they crossed the Transvaal border and headed in the direction of Tolstoy Farm. Earlier, some white men had threatened to shoot them on sight but while many stared at the strange army, no one attacked. After they had set up camp the first night and Gandhi was preparing for bed, a police officer approached. "I have a warrant of arrest for you," he said.

"When?" asked Gandhi.

"Immediately."

Gandhi roused one of his aides and told him to continue the march without him. But he was freed on bail and returned to the miners the following day. On November 8, as he was distributing bread and marmalade to the marchers, he was again arrested, this time by a magistrate. "It seems I have been promoted," he said wryly.

Again he was released on bail and returned to the march. The authorities in the Transvaal began to grow uneasy. They had expected Gandhi's arrests to disorganize his followers, but no one panicked. The police waited for violence which they could return with violence, but under Gandhi's teaching, the men remained determinedly peaceful. "How long can you harass a peaceful man?" wrote Gandhi. "How can you kill the voluntarily dead?"

On November 9, Gandhi was arrested for the third time in four days. The following day the marchers were halted, put aboard trains, and shipped back to Natal. On November 11, Gandhi was sentenced to nine months at hard labor. Three days later he was found guilty on another charge and sentenced to another three months. His chief aides were imprisoned with him. The Indians in South Africa wanted Gandhi to stay until all their demands were met, but Gandhi felt he had done all he could. After twenty years in South Africa it was time to return to India. He had gained specific relief for the Indians, but more important, he had evolved a new means for dealing with evil. He had proved that under certain circumstances the force of truth, or satyagraha, was a priceless and matchless weapon. In South Africa it had eliminated the worst of the anti-Indian abuses. In India it was to crumble an empire and create a new nation. Just before Gandhi left South Africa he gave Jan Christian Smuts a pair of sandals he had made while in prison. Years later Smuts said, "I have worn these sandals for many a summer ... even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man."

To Serve is My Religion:-

No matter what Gandhi did for humanity he felt it was not enough. "To serve is my religion," he once said. He wanted to free men politically, restore them spiritually, and heal them physically. When plague erupted in India during his brief visit there; he inspected the quarters of the poor and sick for cleanliness and nursed his dying brother-in-law. When a leper came to his door in Natal he dressed the man's sores. He worked in a hospital for two hours every morning, and when his third son was born in South Africa he cared for the infant himself. He even delivered his fourth and last son because the midwife was late.

Gandhi liked to live simply and independently, eating mostly fresh fruits and nuts and starching his own shirts. After a white barber refused to give him a haircut, he bought barber's shears and cut his hair himself.

When the Boer War exploded in 1899, Gandhi's sympathy lay with the Boers, but he remained loyal to the British. He felt that since he demanded rights as a British subject he was obliged to participate in the war on behalf of the Empire. He organized eleven hundred Indians into a British ambulance corps. Frequently they had to haul the wounded off the field in the direct line of fire, and it was not unusual to carry casualties twenty or twenty-five miles a day in stretchers. Gandhi's ambulance corps won begrudging admiration from the British. When the corps was disbanded and replaced by British units, Gandhi and some of the other leaders received medals. In 1901 Gandhi decided that if he remained in South Africa he would simply become a prosperous attorney and so the time had come for him to go home to work for India. He left Natal promising that if the Indians needed him within a year he would come back. He was showered with costly jewels and ornaments as farewell gifts but he put them in a bank to be used as a trust fund to meet community needs.

Back in India, Gandhi traveled a great deal and attended the annual meeting of the Indian National Congress, the only national political party in the country. He found the delegates indifferent, the sanitation insufferable, and the movement lacking vision or direction. Nevertheless, he had decided to settle in Bombay, practice law, and enter politics when a cablegram came from South Africa. "Chamberlain expected here," it said. "Please return immediately." Gandhi left his wife and children in Bombay and returned to South Africa to resume his crusade.Though he failed to move Chamberlain in Natal, Gandhi followed him to the Transvaal to present the complaints of the Indians there. This time the authorities would not even permit him to see Chamberlain, and Gandhi soon realized that the condition of the thirteen thousand Indians in the Transvaal was worse than in any other part of South Africa. Gandhi decided to remain there and set up a law office in Johannesburg to work for his people.

The Salt March:-

|

On March 2, Gandhi wrote the Viceroy politely indicting the British for their crimes against India and warning that unless some of the wrongs were righted he would begin his civil disobedience campaign in nine days. The Viceroy's secretary acknowledged the letter coldly; the British conceded nothing. Gandhi commented, "On bended knee I asked for bread and I received stone instead."

|

On March 12, after prayers, Gandhi and seventy-eight disciples, both men and women, left the satyagraha ashram and headed south on foot. "We are marching in the name of God," said Gandhi.

Along the way peasants prostrated themselves in the dust to receive the blessing of the Mahatma's presence and kiss his footprints. Each day more volunteers joined the small army until it swelled to several thousand. Leaning on a long staff, sixty-one-year-old Gandhi led the marchers to a place on the seashore called Dandi. It was a two-hundred-mile trek, and Gandhi, a superb dramatist, covered it in twenty-four days in an atmosphere of mounting veneration and excruciating suspense.

Gandhi reached Dandi on April 5. He and his followers prayed all that night. At dawn he walked into the sea. Then he returned to the shore and picked up a pinch of salt. This was the signal all India had awaited. Gandhi had defied the salt laws and was telling his countrymen to do the same. This was his chosen path of civil disobedience without violence.

"It seemed as though a spring had been suddenly released," wrote Nehru. All over India the war of independence began. The armor of the Indians was the teaching of Gandhi and their weapon was common salt. On the coast they produced it illegally; in the interior they bought and sold it illegally. The exasperated British responded with mass arrests and beatings, but they could not rewind the spring.

Purifying India:-

In May of 1933 Gandhi fasted twenty-one days for personal reasons. The British, still nervous about his dying in their custody, released him from prison. On August 1, however, he was rearrested for a civil disobedience act. He was released three days later, rearrested for disobeying a court order, and finally freed again when he began another fast.

For the next six years Gandhi stayed out of jail and out of politics, though his influence with the Congress party was so great that it did nothing without his approval and all the members religiously wore homespun.

He was in his late sixties now, slender, toothless, half-naked, with a toothbrush moustache, large round spectacles, jutting ears, and a shaved head. He once protested that a cartoonist had made his ears too big, then admitted he didn't know how big they were because he no longer looked at himself in a mirror. Still seeking to purify India, Gandhi toured the country tirelessly, denouncing untouchability and trying to restore the peasants' faith in themselves. He objected to extremes of wealth and poverty and wanted to make every village self-sufficient, producing its own food and clothing its own people. The peasants came to him for his blessings and his advice on food, health, and sex. When he passed, they kissed the roads he trod upon.

But as Gandhi's shadow glided gently over the dusty paths of India a more brutal image seized the world's attention. Adolf Hitler was igniting the second great war. Still Gandhi preached ahimsa, or nonviolence. He would rather be killed than kill, he declared.

When the Nazis began to exterminate the Jews, Gandhi advised nonviolence and voluntary sacrifice. "I can conceive the necessity of the immolation of hundreds, if not thousands, to appease the hunger of dictators," he said. For reasons that had nothing to do with Gandhi but were graven in their own heritage most Jews did respond nonviolently. Not hundreds or thousands were murdered, but six million, and the slaughter ceased only when the Nazis were destroyed. If Gandhi had earlier proved that nonviolence is sometimes an effective weapon, the Nazis proved it is effective only against a civilized opponent.

|

India had been tasting independence for about twenty years; she had felt free ever since the war began. When news of the arrests became known, the Indians erupted against the British in acts of violence, murder, and rebellion across the country.

The British blamed Gandhi, who was powerless to do anything because they held him in prison. If he had not been arrested he would have sought a nonviolent outlet for his people similar to the Salt March. Imprisoned, he could do nothing but pray. For a time he was not even aware of the turmoil, because he was not permitted to read any newspapers.

Pained by British accusations that he was somehow responsible for the thing he hated most, Gandhi announced he would fast twenty-one days. The Viceroy dismissed the announcement as "a form of political blackmail." Nevertheless the British offered to free him. He refused and fasted in jail.

He was seventy-two years old and everyone, including his wife Kasturbai, who was in prison with him, expected him to die. But somehow he survived, and before he was released it was Kasturbai who died, on February 22, 1944, her head resting in her husband's lap. They had been married over sixty years, and Gandhi wrote, "I feel the loss more than I had thought I should."

Not long after, Gandhi was struck down by malaria, followed by a severe intestinal disease. The British, still fearful of the consequences of his dying in their custody, freed him on May 6, 1944. As soon as he was well, Gandhi began a series of frustrating, fruitless conferences with the Moslem leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who, now that India was on the threshold of independence, was insisting that a separate Moslem state of Pakistan be carved out of it.

Hindus in India outnumbered Moslems three to one. Most of the Moslems were, in fact, Hindus who had been converted to Islam by various conquerors. But the Moslems felt themselves to be an oppressed minority; they feared that an India ruled by Hindus would deny them equal opportunities in employment, education, and basic liberties. Their solution was to establish a separate Moslem state and their spokesman was Jinnah.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah was as different from Gandhi as Satan is from God. Where Gandhi's weapon was love, Jinnah's was hate. Years before, Jinnah had been a leader of the Congress party but he had abandoned it in disdain when Gandhi took control and tried to make it more democratic. Hating Gandhi and believing himself the victim of countless slights, he became leader of a party called the Moslem League, which was anti-Gandhi, anti-Congress, and anti-India.

To win peasant support for a separate Moslem state, Jinnah enflamed the Hindu-Moslem religious hatred that always simmered beneath India's surface. Gandhi, who usually spoke kindly even of his enemies, called Jinnah "an evil genius" and a "maniac." For the Mahatma there could be no Hindu nation or Moslem nation, but only an Indian nation. "I find no parallel in history for a body of converts and their descendants claiming to be a nation apart from the parent stock," he wrote. On another occasion he told Jinnah, "You can cut me in two if you wish but don't cut India in two." Jinnah would have been happy to do both.

World War II ended during the summer of 1945, and the Labour Party replaced Churchill's Conservatives in office. The new government made it clear it wanted "an early realization of self-government in India."

The Assassination:-

On January 30th, 1948, he was walking slowly from his home to attend a prayer meeting when a thirty-nine years old Hindu called Nathuram Godse who mistakably thought Gandhi was harming the Hindus by being friendly to Muslims shot the Great Soul after respectfully bowing to him. (Click on picture for video) A few minutes later a man came out to the waiting crowd and announced that the little old man who sacrificed with all he had for his country, who reshaped the lives of many, who changed the path of the world, who inspired -and still will inspire- mankind till the end of the world was dead.

Sabarmati Ashram

The Three Mystic Monkeys:-

Sabarmati Ashram

| |

| Sabarmati Ashram

After Mahatma Gandhi's return from South Africa to India, the choice of settling down in India fell upon the banks of the Sabarmati River, near Ahmedabad in Gujrat. This was the Sabarmati Ashram and in Gandhi's words.."A place for taking training for National service for the community and the country."

The eleven vows followed in the Ashram were:

|

The Three Mystic Monkeys:-

|

| Mahatma Gandhi..The Three Mystic Monkeys !

Gandhiji used simple and clean but beautiful stones, as his paperweights. His three monkeys made of china clay, were his favourite. He kept them to remind him to speak the truth.

In those days, it was common that snakes and scorpions were seen in the ashram. While sleeping, Bapu used to keep some pottasium,bandage,some thread and a blade by his side, so that if anybody in the Ashram were bitten they could be treated immediately. The snakes were not killed, but were left back in the forest.

His whole lifestyle was based on the concept of 'good karma'. The holy 'Gita', was always an inspiring motivation for his thoughts and actions in his life.

The three monkeys were symbolic of ' See No Evil; Hear No Evil and Speak NO Evil !, which meant: 1. Do not tolerate any evil being done around you. 2. Do not participate in any wrong exploitation or sinful talk. 3. Do not speak ill about others and do not harm any beings.

|

Mahatma Gandhi Quotes:-

- The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.

- Where there is love there is life.

- First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

- First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

“Your beliefs become your thoughts,

Your thoughts become your words,

Your words become your actions,

Your actions become your habits,

Your habits become your values,

Your values become your destiny.”

Your thoughts become your words,

Your words become your actions,

Your actions become your habits,

Your habits become your values,

Your values become your destiny.”

Books by Mahatma Gandhi:-

* Autobiography : My Experiments With Truth

*All Men Are Brothers (Complete Book Online)

*Character & Nation Building

*Collected Works Of Mahatma Gandhi (Vol. 1 to 100) (H.B)

*Constructive Programme

*Diet & Diet Reform

*Discourses On Gita

*Essential Work of Mahatma Gandhi (Vol. 1)

*Ethical Religion (Complete Book Online)

*Gandhi For 21st Century, By Anand T. Hingorani (Ed.), Vol. 1 to 24

(Compilation of Gandhi's Philosophy )

*Gandhiji Expects

*Gita According To Gandhi

*Hind Swaraj Or Indian Home Rule

*India Of My Dreams

*Industrial And Agrarian Life And Relations

*Key To Health (Complete Book Online)

*Mohanmala

*My God

*My Religion

*Nature Cure

*Panchayat Raj

*Pathway To God

*Prayer

*Ramanama

*Satyagraha In South Africa

*Selections From Gandhi (Complete Book Online)

*Self Restraint Vs. Self Indulgence

*The Book of Gandhi Wisdom

*The Essence of Hinduism

*The Essential Writings of Mahatma Gandhi

*The Gandhi Reader

*The Law And The Lawyers

*The Mind Of Mahatma Gandhi

*The Selected Works Of Mahatma Gandhi (Vol. 1 to 6)

*The Way To Communal Harmony

*The Words Of Gandhi

*Towards New Education

*Trusteeship

*Truth Is God

*Unto This Last

*Village Industries

*Village Swaraj

*Young India

No comments:

Post a Comment